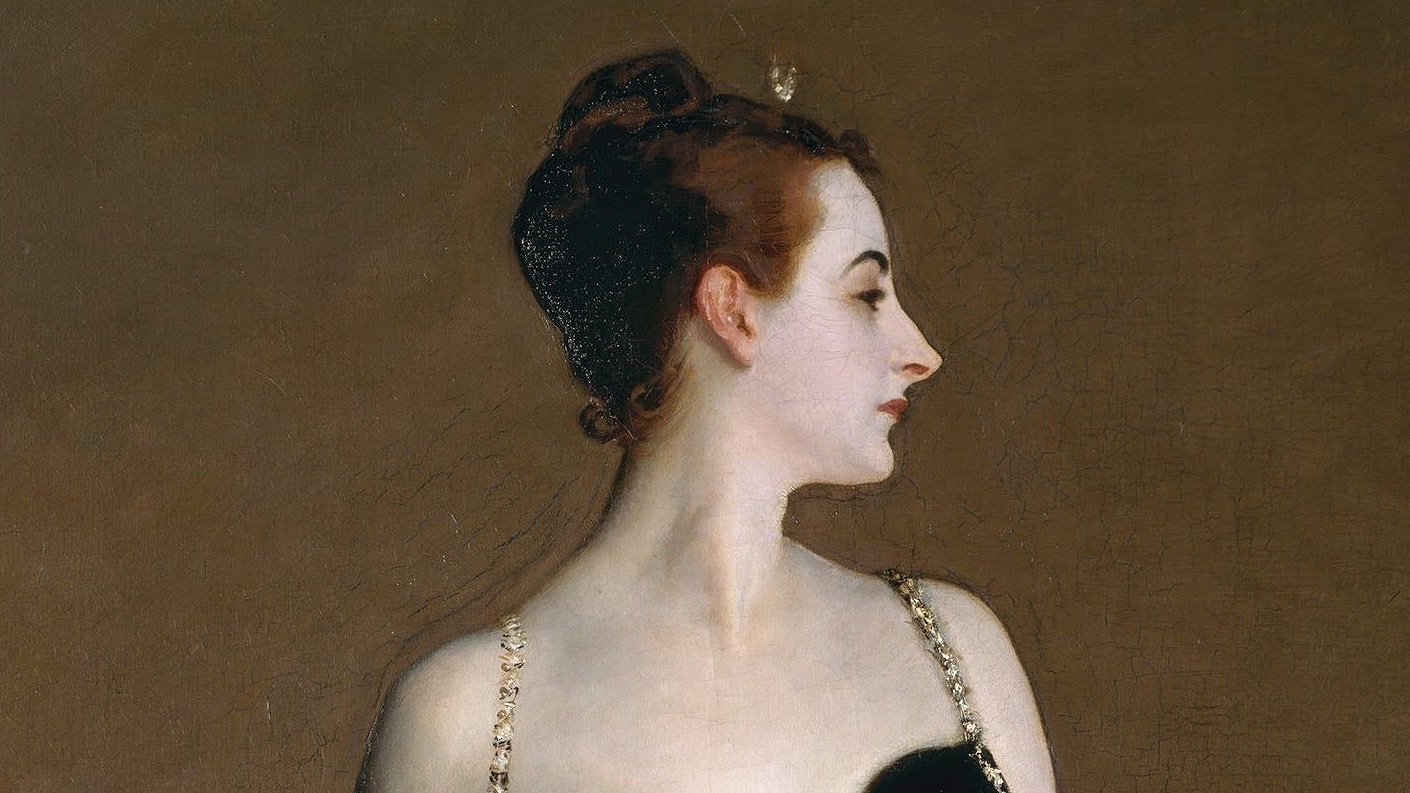

Upon unveiling Madame X at the Paris Salon in 1884, John Singer Sargent hoped to establish his reputation as a portraitist.

Yet critics shared no accolades here. The Times called her “bluish coloring atrocious,” whereas artist (and distant cousin) Ralph Curtis remarked “she looked decomposed.” Some viewers even cried at the horror of her appearance, both sexualized yet stiff, her skin artificially colored with lavender powder.

But the subject of Madame X, Virginie Amelie Gautreau, had prided herself on this unusual coloring for years. The daughter of a Louisiana plantation heiress and a Confederate solider, her arrival in France followed the end of the Civil War. Her father’s death at the Battle of Shiloh expedited their immigration out east, where the 8-year-old Virginie enjoyed a Parisian education. There, she mingled with high society, her own debut as socialite awaiting a decade later.

Making her official debut was no simple task, however. Socialites in Victorian Paris were plentiful; how could one stand out? So Virginie, now married to French banker Pierre Gautreau, sought out a signature look that no other Parisienne dared to wear.

As explained in Stripped: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X by Deborah Davis:

The author pays little attention to the focal point of her makeup, however: Her powdered, lavender skin. Used to counteract the warmth of candlelight, she dazzled contemporaries with her whiteness. Her delicate curves and Romanesque nose, inherited from her Italian-American father, lended her an ancient beauty.

But, more importantly, her statuesque beauty drove artists wild. As explained by art student Edward Simmons in The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris by David McCullough:

Her head and neck undulated like that of a young doe, and something about her gave you the impression of infinite proportion, infinite grace, and infinite balance. Every artist wanted to make her in marble or paint…

That included Sargent, who first met her in 1881. Enamored by her beauty – a platonic lust at first sight – he feverishly petitioned to paint her. She acquiesced. In the midst of painting her, however, her powdered skin proved difficult to portray. Though it appeared a creamy white in candlelight, the natural light exposed its true color: A lifeless, cold lavender.

But what did she use? Here begins a mystery that I’ve obsessed about for weeks. Although Waldamar Januszczak references her love of rice powder in his documentary of John Singer Sargent and Walter Sickert, that doesn’t explain the lavender hue.

As it turns out, the biggest hint of its source comes from Sargent himself. Let’s explore it.

Madame X’s Mysterious Face Powder

In a letter to writer and feminist Vernon Lee in 1883, Sargent wrote about his next big portrait – an unnamed woman of “great beauty,” later revealed to be Madame Gautreau. But here’s where he reveals a clue about her mysterious powder:

Do you object to people who are fardees to the extent of being a uniform lavender or blotting-paper colour all over? If so you would not care for my sitter. But she has the most beautiful lines and if the lavender or chlorate-of-potash-lozenge colour be pretty in itself I shall be more than pleased.

From “John Singer Sargent and Vernon Lee” by Richard Ormond for Colby Quarterly, 1970.

In modern times, we know chlorate of potash by a different name: Potassium chlorate. It’s commonly used in explosives, safety matches and insecticides – real dangerous stuff. But in Victorian Paris, it somehow finagled its way into a plethora of products, including lozenges, cough syrup, and yes, cosmetics.

In the article “Painting Skin” by Susan Sidlaukis, published in American Art, she notes the danger of using powders containing potassium chloride. The year Madame X debuted, knowledge of its toxicity was public knowledge.

“By 1884, it was widely known that the metallic compound of chlorate of potash, the basis for Gautreau’s lavender powder, could be toxic for its users,” she writes. “At a fraction of its nineteenth-century strength in cosmetics, it is used today in insecticides.”

That probably didn’t deter Gautreau’s use of it, however. Papers at this time lamented women risking death to look beautiful, though it focused on their love of lead face paint.

But Gautreau’s makeup routine routine probably didn’t lack lead. In addition to the rouge she used to redden her ears, of which commercial preparations were lead-laced, she may have applied a slick base underneath the lavender powder. Doing so gave the rice powder something to cling to.

Unfortunately, popular choices at this time included ceruse, a mixture of water, lead, and vinegar, favored by monarchs such as Queen Elizabeth of England. Moisturizer was a safer alternative also used, but it didn’t offer the same coverage.

Which option did Virginie choose? Nobody knows, but for her health’s sake, I hope it was moisturizer.

As for Sargent’s painting of her, it proved disastrous for the young socialite. Her signature lavender pallor, once the envy of many, now left her reputation in ruin. Distraught, she supposedly broke all of the mirrors in her home. In the meanwhile, Sargent left Paris to paint in England.